Diagnostic tests for diseases and drugs are not perfect. Two common measures of test efficacy are sensitivity and specificity. Precisely, sensitivity is the probability that, given a drug user, the test will correctly identify the person as positive. Specificity is the probability that a drug-free patient will indeed test negative. Even if the sensitivity and specificity of a drug test are remarkably high, the false positives can be more abundant than the true positives when drug use in the population is low.

As an illustrative example, consider a test for cocaine that has a 99% specificity and 99% sensitivity. Given a population of 0.5% cocaine users, what is the probability that a person who tested positive for cocaine is actually a cocaine user? The answer: 33%. In this scenario with reasonably high sensitivity and specificity, two thirds of the people that test positive for cocaine are not cocaine users.

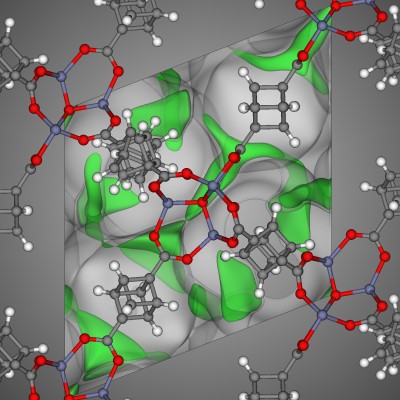

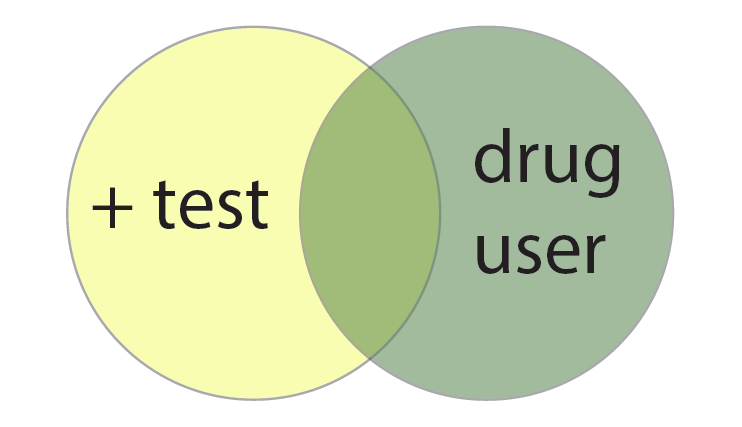

To calculate this counter-intuitive result, we need Bayes’ Theorem. A geometric derivation uses a Venn Diagram representing the event that a person is a drug user and the event that a person tests positive as two circles, each of area equal to the probability of the particular event occurring when one person is tested: \(P(\mbox{user})\) and \(P(+)\), respectively. Since these events can both happen when a person is tested, the circles overlap, and the area of the overlapping region is the probability that the events both occur, \(P(\mbox{user and }+)\).

We write a formula for the quantity that we are interested in, the probability that a person is indeed a drug user given that he or she tests positive for drugs, \( P(\mbox{user}|+) \) by acknowledging that we are now only in the world of the positive test circle. The +’s that are actually drug users can be written as the fraction of the ‘+ test’ circle that is overlapped by the ‘drug user’ circle:

We bring the sensitivity into the picture by considering the fraction of the drug users circle that is occupied by positive test results:

Equating the two different ways of writing the joint probability \(P(\mbox{user and }+)\), we derive Bayes’ Theorem:

We already see that, in a population with low drug use, the sensitivity first gets multiplied by a small number, \(P(\mbox{user})\). Since we do not directly know \(P(+)\), we write it differently by considering two exhaustive ways people can test positive, namely by being a drug user and by not being a drug user. We weigh the two conditional events by the probability of these two different ways:

As people are users or non-users, \(P(\mbox{user})+P(\mbox{non-user}) = 1\). Similarly, we can bring the specificity \(P(- | \mbox{non-user})\) into the picture by considering that non-users tested will be either positive or negative.

\(P(+)\) can be computed by these known values as \(P(+)=0.0149\).

Finally, using Bayes’ Theorem, we calculate the probability that a person that tests positive is actually a drug user:

The reason for this surprising result is that most (99.5%) people that are tested are not actually drug users, so the small probability that the test will incorrectly identify a non-user as positive results in a reasonable number of false positives. While the test is good at correctly identifying the cocaine users, this group is so small in the population that the total number of positives from cocaine users ends up being smaller than the number of positives from non-drug users. There are important implications of this result when zero tolerance drug policies based on drug tests are implemented in the workforce1.

The same idea holds for diagnostic tests for rare diseases: even for a test with a high reported sensitivity and selectivity, the number of false positives could be greater than the number of positives for people that actually have the disease.

I wrote another article in the Scientific American Blogs with my supervisor at Berkeley about false positives for terrorist watch lists; similarly, good algorithms for identifying terrorists likely have more false positives than true positives because terrorists are likely rare in our population.

Below is a YouTube video deriving Bayes’ Theorem again for two general events A and B.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayes’_theorem See ‘drug testing’. This is where I obtained the example.

1If each test is an independent trial, one could simply test a person multiple times. If the test results in + each time, this gives us more statistical confidence that this person is a drug user. On the other hand, one can imagine that if there is something biologically different about a given person or something that they eat that triggers the false positive, testing multiple times will not yield greater confidence.

comments powered by Disqus