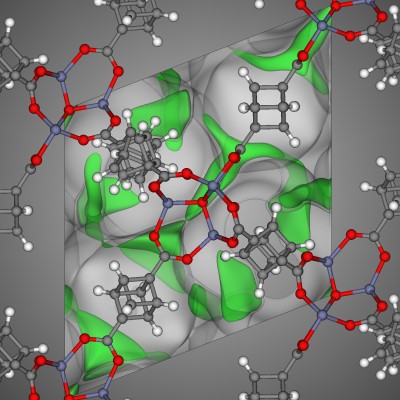

The phrase ‘tip of the iceberg’ originates from the fact that most of an iceberg floating in the ocean is beneath the surface of the water. With a back-of-the-envelope calculation, we can estimate what fraction of a free-floating iceberg is above the surface.

Consider when an object (the iceberg) is immersed in a fluid (the salty water of the ocean). Gravity exerts a downward force on the object. As not all objects sink, an opposing force on the object is at work. This force that is strong enough to cause some objects to float is called a buoyant force.

A buoyant force is the force exerted on the immersed object by the fluid, in the opposite direction of gravity. Actually, this force is a consequence of gravity too– the exertion of gravity on the fluid. Gravity pulls down on the molecules of the fluid; molecules deep in the fluid can “feel” the weight of the molecules on top of them. As a consequence, the pressure in the fluid increases with depth. You can feel the higher pressure on your ears when you swim to the bottom of a swimming pool. Similarly, as the air is a fluid, your ears pop because of the lesser pressures at high elevations, like in an airplane or on a mountain.

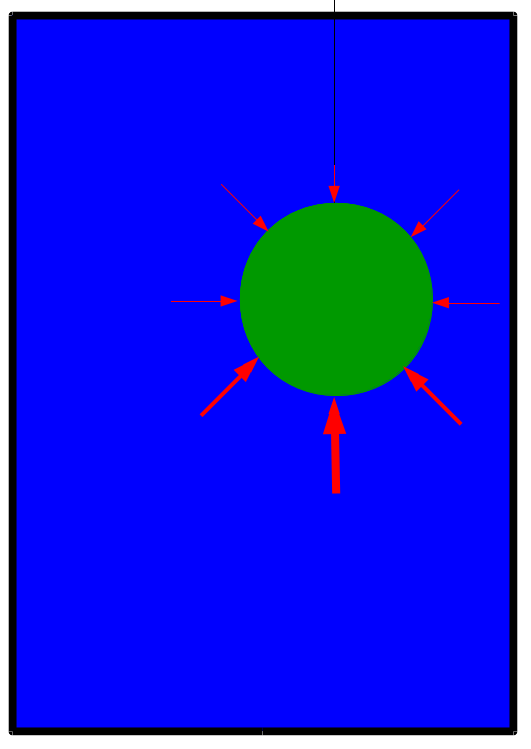

How does this increase of pressure with depth give rise to the buoyant force? Imagine that we tie a green marble to a thread and suspend it in a glass of water:

The fluid would exert a force on the marble at every point on its surface in a direction perpendicular to the surface (red arrows)– this is the pressure of the fluid at work. However, the pressure at the bottom of the fluid is greater than the pressure at the top of the fluid. As a consequence, the fluid is exerting a net upward force on the object. The arrows at the bottom are thicker than the arrows at the top to represent the magnitude of the force at the greater depth to be larger. Whether an object will float or sink depends on how the magnitude of the buoyant force compares with the downward gravitational force on the object.

Archimedes’ principle quantifies the strength of this buoyant force, and it depends only upon the volume of fluid that the object displaces when it is submerged (partially or fully). I derive Archimedes’ principle at the end.

An object that is fully or patially submerged in a fluid experiences an upward force by the fluid equal to the weight of the fluid that it displaces.

-- Archimedes’ Principle

Back to the iceberg.

The density of ice is kg/m3, and the density of salty seawater is around kg/m3. Since seawater has a higher density than ice, the weight of the ice is less than that of the equivalent volume of seawater; Archimedes’ Principle tells us that an iceberg will float, then, since the buoyant force on the iceberg when fully submerged is greater than the weight of the iceberg.

Let’s finally calculate the fraction of the iceberg that will be submerged when it floats. The iceberg will be at equilibrium when the buoyant force by the seawater is equal to the gravitational force on the iceberg itself. Let be the volume of the iceberg and be the fraction of the iceberg that is beneath the surface, for which we will solve. So is the volume of iceberg that is submerged.

The force due to gravity on the iceberg is , its mass times the acceleration due to gravity m/s. The buoyant force on the iceberg is , since this is the weight of the seawater displaced by the iceberg with our submerged volume of ice .

Equating these two forces and solving for , we get the fraction of the iceberg that is submerged as the ratio of the density of ice to the density of seawater.

So 89% of a free-floating iceberg is submerged beneath the surface of the ocean; we only see 11% of it above the surface of the ocean. That the tip of the iceberg is just 11% is a result of a simple calculation.

As an intuition check, if we instead consider an object with a density larger than that of seawater, we would get , indicating that the object would sink since we can’t submerge more than 100% of an object!

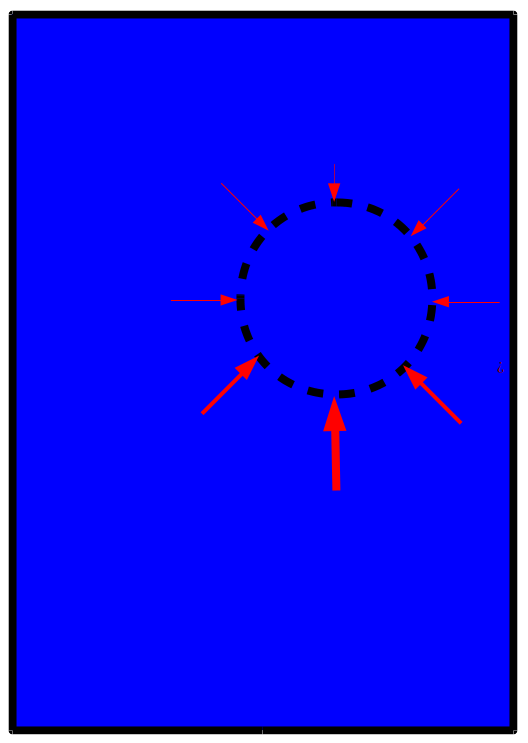

Mathematical derivation of Archimedes’ Principle

Consider a hydrostatic fluid with a pressure and a closed volume of fluid, drawn with dashed lines in the figure above. The pressure increases with depth according to the following equation:

Here, is the density of the fluid.

As pressure acts normal to the surface of the volume, the net buoyant force on the volume of fluid by the surrounding fluid is a surface integral over the boundary of the volume:

Here, is the outward unit normal vector to the surface; the negative sign is to account for pressure acting in the opposite direction of . Gauss’s divergence theorem relates this surface integral to the volume integral:

Now, we are integrating over the entire volume . Using the equation for above, and the integral over the volume becomes:

if the density of the fluid is spatially uniform. The value is just the volume of !

From the perspective of the fluid outside of the volume that we considered here, it does not matter if an object is inside or if this is fluid1. Thus, this is the buoyant force exerted on an object immersed in a fluid with density : an upward force equal to .

1 Yeah, yeah, we are ignoring surface tension here, but I think this force is negligible on an iceberg.

Thanks to Aaron Bradley for the idea for this blog post!

comments powered by Disqus